“I need the viewer, I need the public interaction. Without a public these works are nothing, nothing. I need the public to complete the work. I ask the public to help me, to take responsibility, to become part of the work, to join in.” — Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Felix Gonzalez-Torres created 20 unique candy works between 1990 and 1993. These generally bright and shiny sculptural accumulations are each composed of a different type of wrapped candy, which have included chocolate, licorice, bubble gum, and lollipops—and each work has a listed ideal weight specified by the artist.

Like most of the artist’s paper stacks—initiated two years earlier and conceptualized as unique works, yet in “endless supply”—viewers can choose to take individual pieces from the displayed artwork and “carry it with them.” A visitor may also consume and savor the sweet confection. As viewers take from the work, its form may change. As Gonzalez-Torres explained, “I need the viewer, I need the public interaction. Without a public these works are nothing, nothing. I need the public to complete the work. I ask the public to help me, to take responsibility, to become part of the work, to join in.”

While not precisely autobiographical in any direct or definitive way, the forms, imagery, and parenthetical titles that appear (and reappear) in Gonzalez-Torres’s art are often infused with personal meaning and political and cultural references and associations. In several of the candy works, the ideal weights correlate to the body weight of a human: including that of the artist and his partner, Ross Laycock. In this way, works such as “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991) and “Untitled” (Lover Boys) (1991) function as personifications or portraits of individuals or couples. When he started making the first paper stacks and candy works, Gonzalez-Torres was facing Laycock’s declining health; “letting go” of the work was a way to learn how to let go, while simultaneously “giving back to the viewer, to the public.” Laycock was diagnosed with AIDS in the late 1980s and died in 1991 from related complications. Gonzalez-Torres died from AIDS-related complications in 1996.

While all of Gonzalez-Torres’s candy works have the capacity to physically change and shift each time they are exhibited, some, such as “Untitled” (USA Today) (1990) and “Untitled” (Placebo) (1991), more overtly invoke larger collective bodies or abstractions. The vast, shimmering array of silver candies in “Untitled” (Placebo) suggests the placebos commonly used in clinical trials for new medications, which often take the form of a sugar pill. While designed to look like a treatment, a placebo is inert. “Beautiful things can be very deceiving,” Gonzalez-Torres asserted. “That’s how most things operate in our culture.”

The artist’s ethereal carpet or pile of sugary candies was initially installed four years after AZT became available in 1987 as the first antiretroviral drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HIV and AIDS. This monumental accumulation of hard candies is a potential summoning of the activism that brought research, clinical trials, and experimental treatment into sharp focus and loudly criticized the priorities of governmental agencies and private sector interests in response to the AIDS pandemic.

In 1989 the Public Art Fund commissioned Gonzalez-Torres to create a work to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. He chose to install an ephemeral monument in the form of an 18-by-40-foot billboard situated at a significant crossroads in Greenwich Village at Seventh Avenue South and Christopher Street, a short walk from the artist’s studio apartment on Grove Street, and a stone’s throw from the famed Stonewall Inn. Two lines of white text traversing the bottom of the black billboard, like a caption or subtitle, read, “People With AIDS Coalition 1985 Police Harassment 1969 Oscar Wilde 1895 Supreme Court 1986 Harvey Milk 1977 March on Washington 1987 Stonewall Rebellion 1969.”

This is a distinctly queer collection of events and dates, indexing milestones in queer liberation while highlighting repression, resistance, and grassroots organizing. The abbreviated history is incomplete, fragmentary, and willfully nonchronological; it makes no effort to be comprehensive or authoritative; its order is decidedly idiosyncratic, and most of the billboard is blank. The black surface provides a space where viewers could project their own imaginary histories, associations, and experiences. As art critic Michael Brenson proclaimed in the New York Times at the time, “You may not even notice the work at first, but once you pick up the ribbon of hard white letters across the memorial blackness, it is hard to forget.”

Ephemerality was a critical component for the artist while considering how best to commemorate a living movement and ongoing struggle. Gonzalez-Torres’s temporary monument was on view in Sheridan Square for six months in 1989, a central location for numerous marches, including official and unofficial events organized as part of New York’s Gay Pride Parade, which drew 150,000 marchers to celebrate Stonewall 20, an anniversary moment also marked by “grief and fear and barely containable rage” due to the mounting AIDS pandemic death toll.

Taking a different approach to the public format, another piece in the billboard body of work, Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (1991) has no text whatsoever, and instead focuses on a black-and-white, closely cropped, monumentally enlarged image of the artist’s bed installed in multiple and diverse outdoor billboard locations. The work premiered as 24 billboards across different New York City locations in 1991, and was accompanied by an indoor billboard that was part of MoMA’s Project Series in 1992. The sharply ambiguous and seductively simple image holds a powerful and melancholic quality captured in the imprint of the absent human bodies that come into focus. The public circulation of such a private image uncovers something akin to intimacy.

Part of the artist’s recurring motif of doubles, “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) (1991) consists of two identical analog clocks displayed side by side so that they are just touching, ideally installed high on a wall, above head height. The pairing of the otherwise generic and unaltered store-bought wall clocks makes for a poignant meditation on love, loss, mortality, and renewal. Gonzalez-Torres once commented, “Time is something that scares me…or used to. This piece I made with the two clocks was the scariest thing I have ever done. I wanted to face it. I wanted those two clocks right in front of me, ticking.” The emotional heft of the artwork hangs on the realization that the perfect lovers depicted will inevitably fall out of synch, and one battery may fail before the other. The clocks must, however, be reset, and synchronicity restored, opening the possibility for perpetual continuation. “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) encapsulates an elegiac beauty encountered in Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s art, a beauty suffused with loss, rage, and the power of love.

C. Ondine Chavoya, art historian and 2023–24 MoMA Scholar, 2025

Works in Collection

12 works

"Untitled"

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1991

"Untitled"

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1987

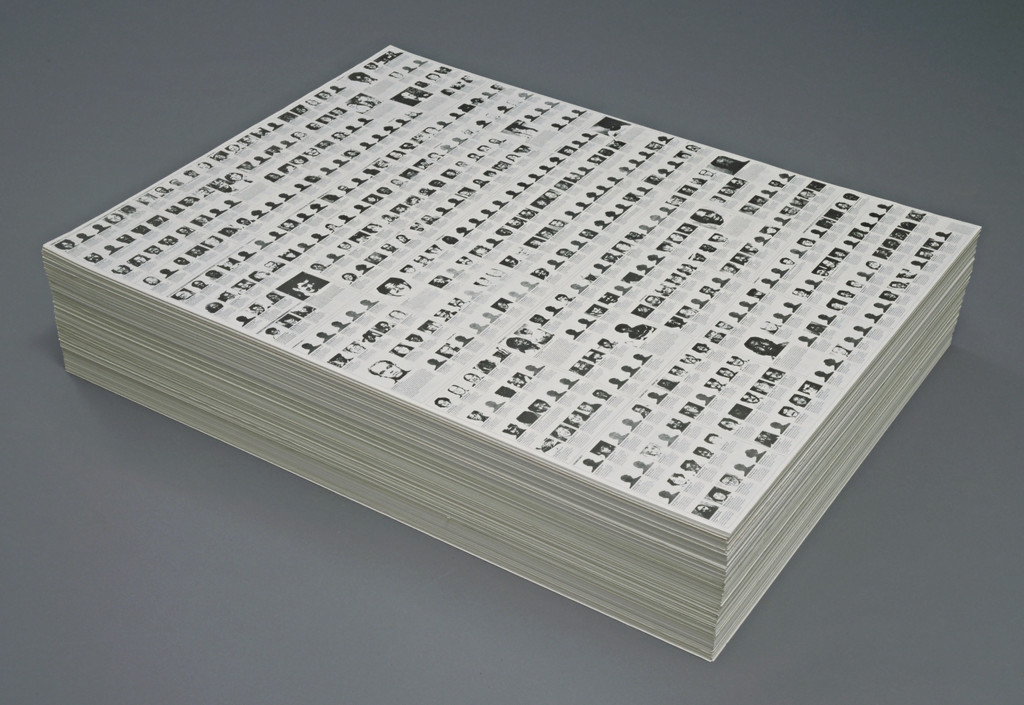

"Untitled" (Death by Gun)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1990

"Untitled" (Perfect Lovers)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1991

"Untitled" (Placebo)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1991

"Untitled" (Supreme Majority)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1991

"Untitled" (Toronto)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1992

"Untitled" (USA Today)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1990

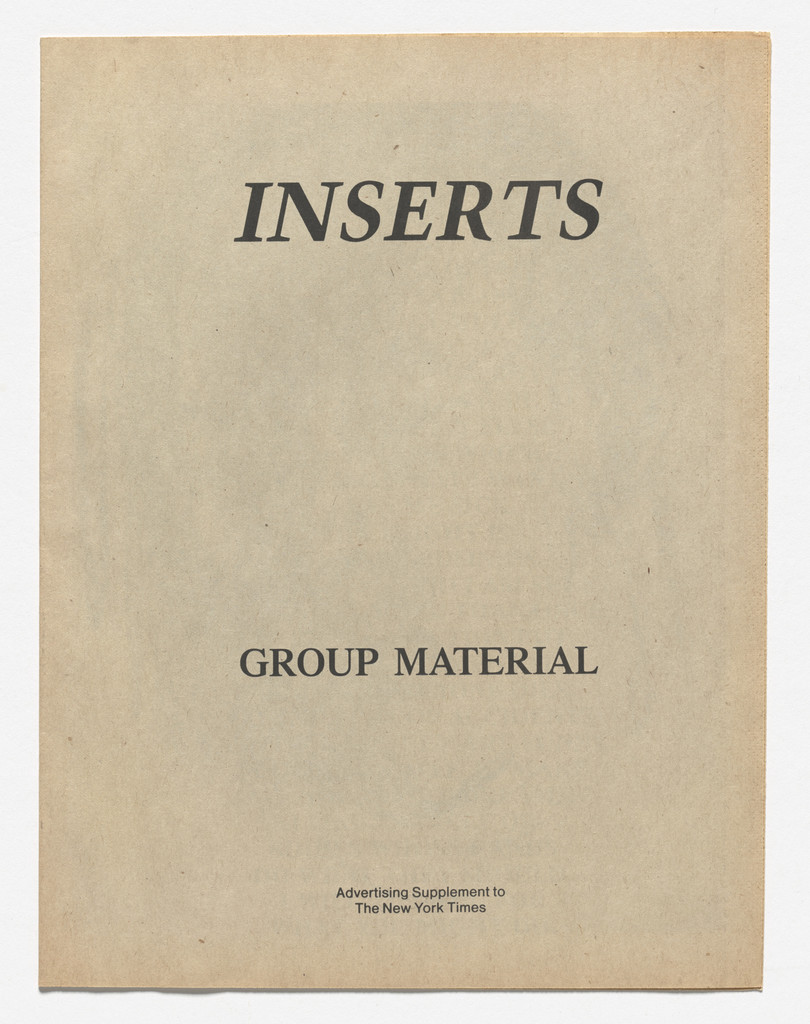

Inserts, an advertising supplement produced for New York ...

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1988

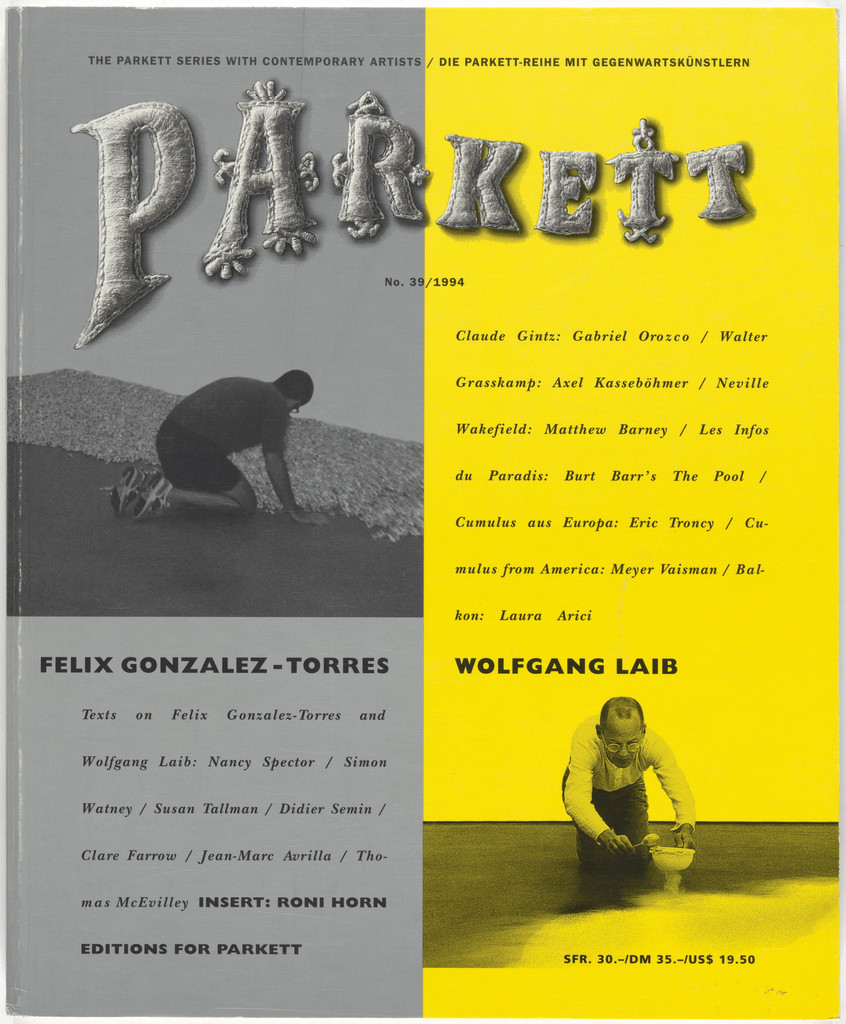

Parkett no. 39

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1994

Untitled (Album)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1992

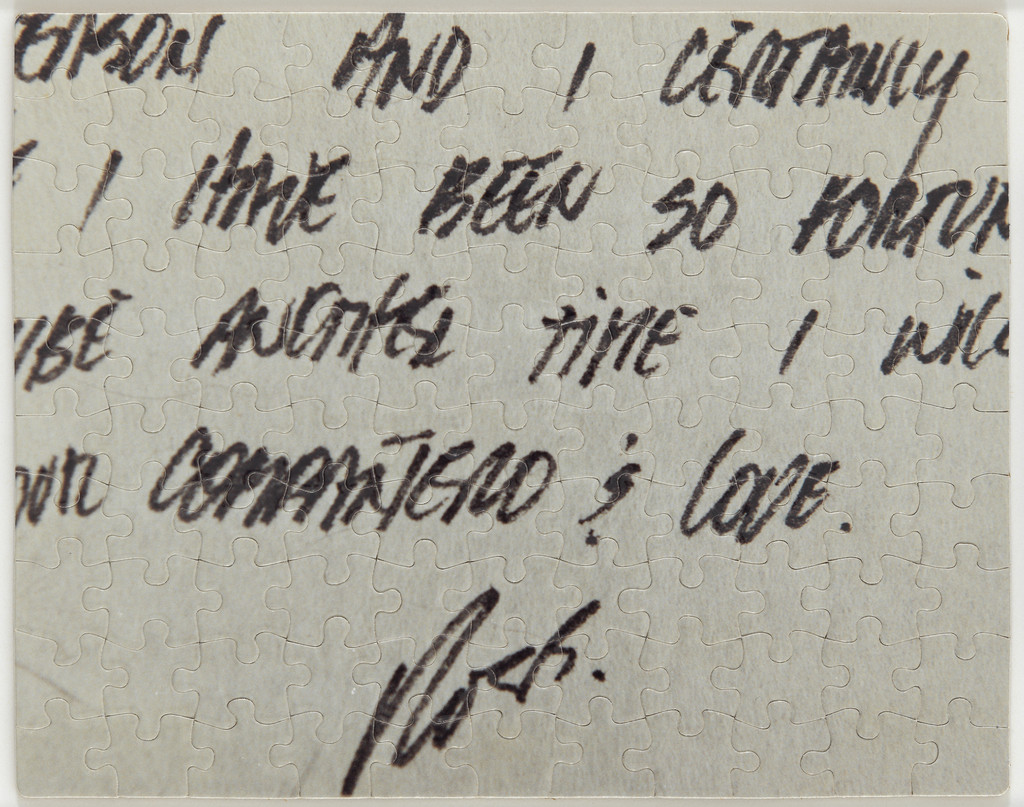

Untitled (Last Letter)

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

1991