Maria Martins’s visceral biomorphic sculptures explore religion, the unconscious, and Amazonian mythologies. Born and raised in Brazil, Martins first studied music before relocating to Paris as a young adult. There Martins married Brazilian diplomat Carlos Martins Pereira e Sousa, whom she accompanied around the globe to Belgium, Ecuador, Japan, and the United States, among other places, before returning to Brazil permanently in 1950. While living in Brussels, she took up sculpture, studying with Belgian sculptor Oscar Jespers. In the ensuing years, as she relocated from city to city, she learned to work in different mediums, from wood to terracotta to bronze. Her itinerant lifestyle enriched her artistic vocabulary and contributed to the stylistic diversity of her sculptures.

When the couple relocated to the US for her husband to serve as ambassador from Brazil, Martins created a makeshift studio in the attic of the Brazilian embassy. In 1941 she presented her first solo exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC. Martins used varied materials to represent themes relevant to Brazilian culture, from Amazonian myths to Catholicism. For Christ, which was included in the exhibition, Martins directly carved jacaranda wood, a material native to Brazil, to create a larger-than-life statue of the religious figure in an unusual posture. Martins’s sculpture depicts Christ with his arms raised overhead, in a gesture of “furious righteousness,” as it was described by MoMA director Alfred H. Barr Jr.

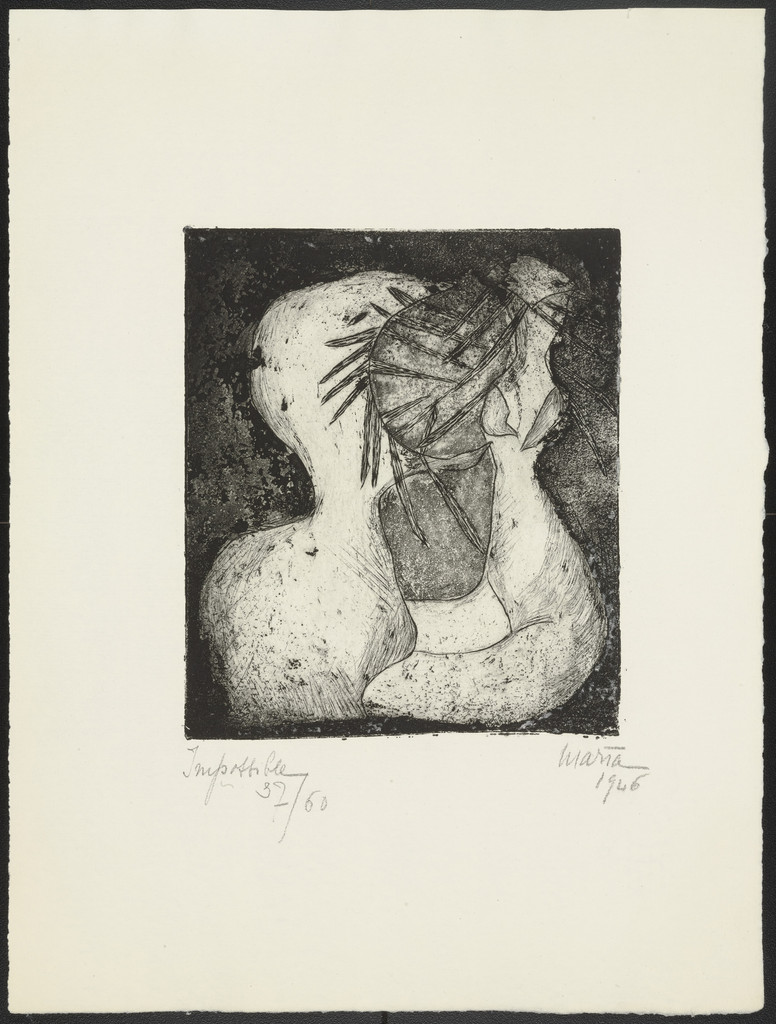

That same year Martins set up a studio in Manhattan, where sculptor Jacques Lipchitz introduced her to bronze casting. This technique became her preferred medium, and she experimented with different casting techniques, patinas, and engravings in subsequent works. She often created the same form in different materials, as in The Impossible, III (1946), one of several versions and part of a larger body of work characterized by writhing, plantlike forms. The spiky tentacles reaching toward each other in this bronze sculpture are locked in an embrace that suggests both opposition and attraction. “The world is complicated and sad—it is nearly impossible to make people understand each other,” Martins said of the work.

In New York City, Martins formed close relationships with key members of the art world, such as Marcel Duchamp and Barr. Martins immediately became a central figure in the city’s cultural scene. In one storied instance, she anonymously donated Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie to MoMA. She had exhibited with Mondrian at Valentine Gallery in Manhattan, and acquired the work when it went unsold.

She also befriended a wider circle of European émigrés who were displaced or had escaped persecution as a result of World War II. Of these new friends, those affiliated with Surrealism, like Andre Breton and Benjamin Peret, were immediately struck by Martins’s sculptures. In two major shows at Valentine Gallery in 1942 and 1943, her works explicitly referenced Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian mythological and religious figures, and stories related to the Amazon. The reception of Martins’s reference to these cultures in the US context was complicated. Her deployment of Indigenous themes in her work satisfied European Surrealist expectations of what Brazilian art could represent; Breton immediately welcomed her to the group after seeing her Amazonia exhibition. However, European Surrealists’ interpretations often flattened her references to Amazonian cultures to a generic understanding of them, as ciphers for a premodern, even irrational world. This dynamic was further complicated by the fact that Martins had never been to the Amazon and had no personal connection to Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous cultures. She invoked these references as part of her own negotiated relationship to Brazilian identity, as someone who lived outside of Brazil for much of her adult life.

Beyond these complex cultural dynamics, Martins’s works from this period do share Surrealism’s fascination with symbolism and the unconscious, as in The Road; The Shadow; Too Long, Too Narrow (1946). Martins transforms bronze into an ethereal material, balancing an elongated figure progressing forward on a thin beam. The “shadow” extends from the walking figure’s foot, blooming into an undulating serpentine form whose limbs reach forward in pursuit of the figure. Martins plays with the notion of the shadow—often an echo of form—instead imagining it as a mythical figure that menaces its counterpart.

Martins returned to her native Brazil at the age of 56 as a central figure in the cultural scene. She helped organize the first Bienal Internacional de São Paulo in 1951 and later won first prize at the 3rd edition, in 1955. Her final public exhibition took place in 1956 at Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, an institution she helped establish after its founding in 1948. However, despite these achievements, her artwork was seen by some peers in Brazil as being out of step with avant-garde movements focused on geometric abstraction that dominated the visual art discourse in 1950s Brazil. Yet it is precisely her art’s resistance to neat categorization that aligned with her steadfast belief in creative freedom and her commitment to making exactly the art she wanted, regardless of what anyone else had to say.

Rachael Remick, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture, 2026

Works in Collection

16 works

Christ

Maria Martins

1941

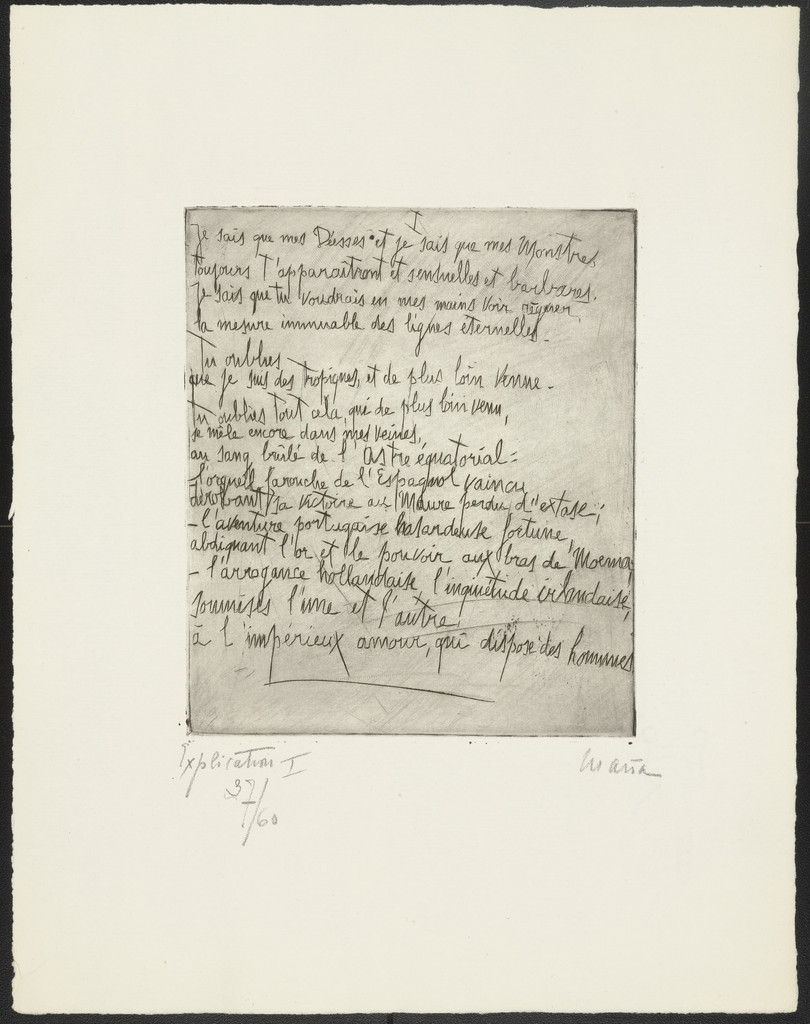

Explanation I (Explication I) from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

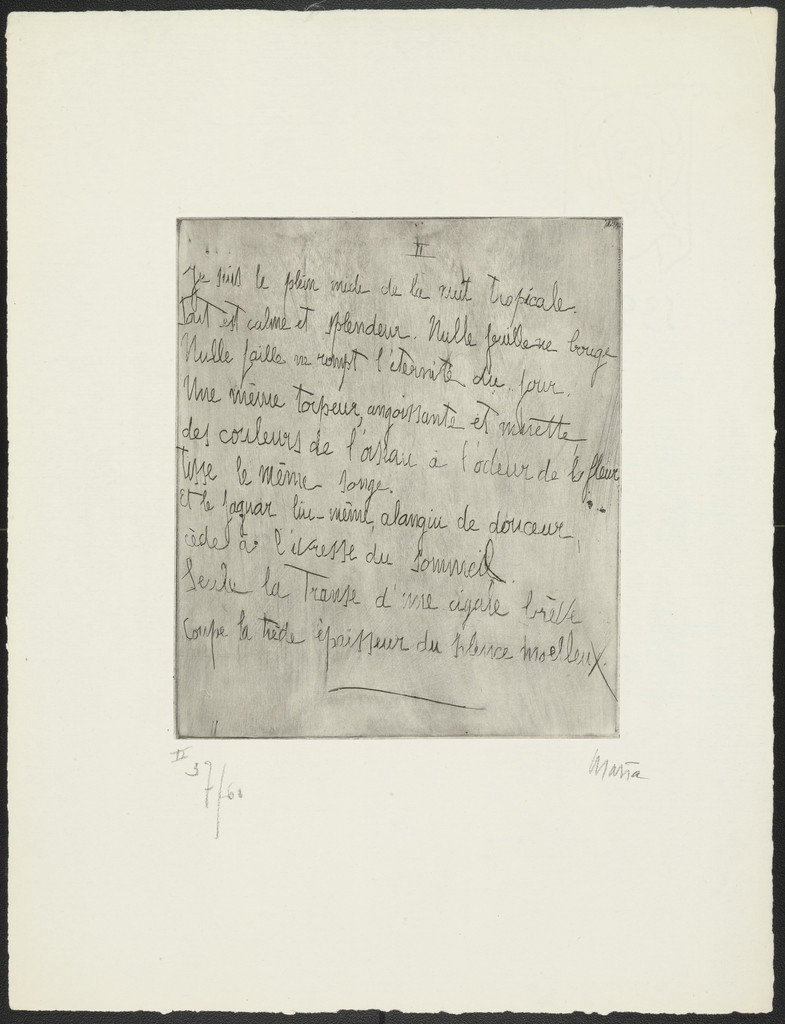

Explanation II (Explication II) from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

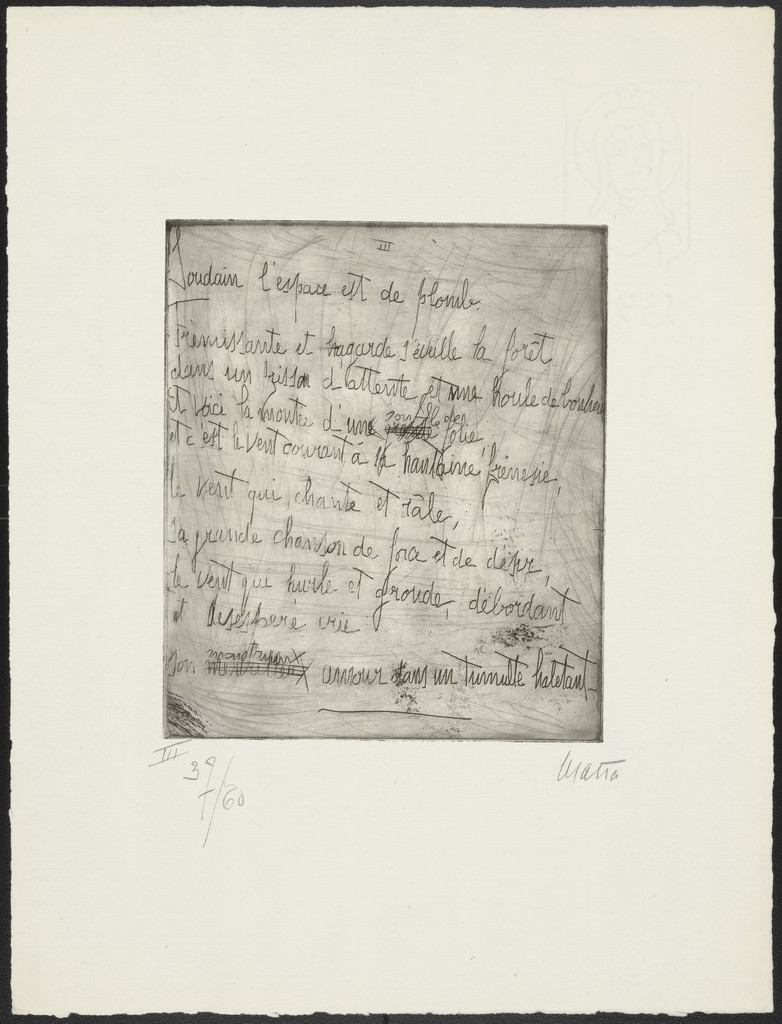

Explanation III (Explication III) from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

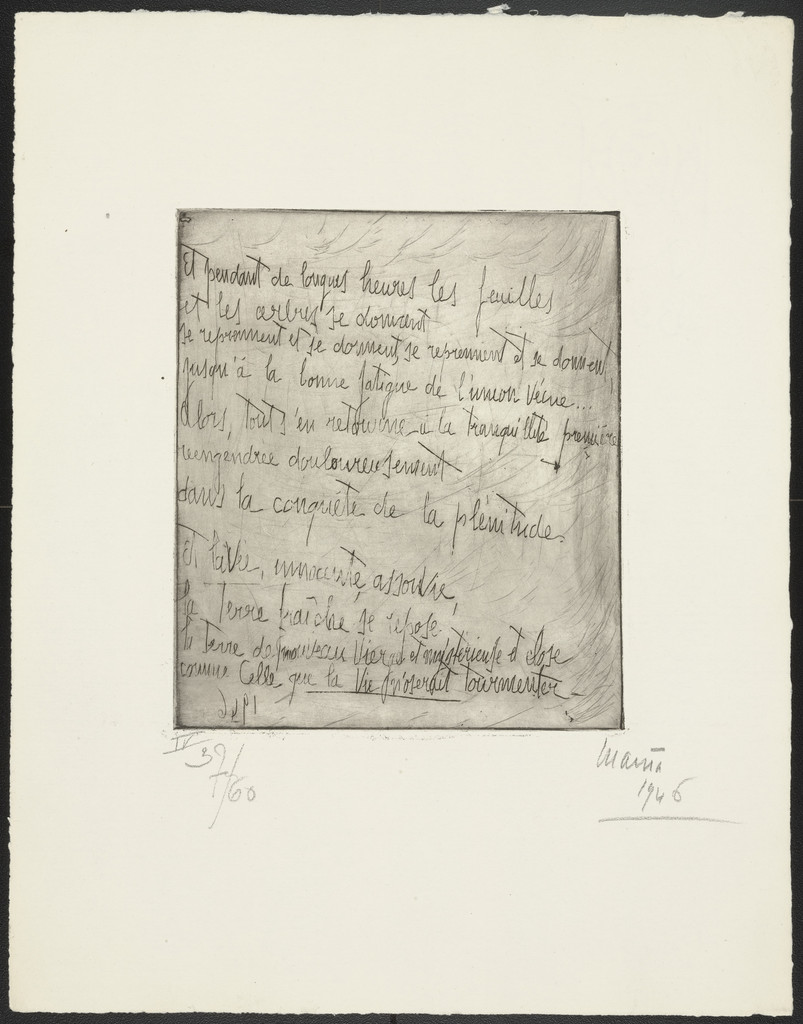

Explanation IV (Explication IV) from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

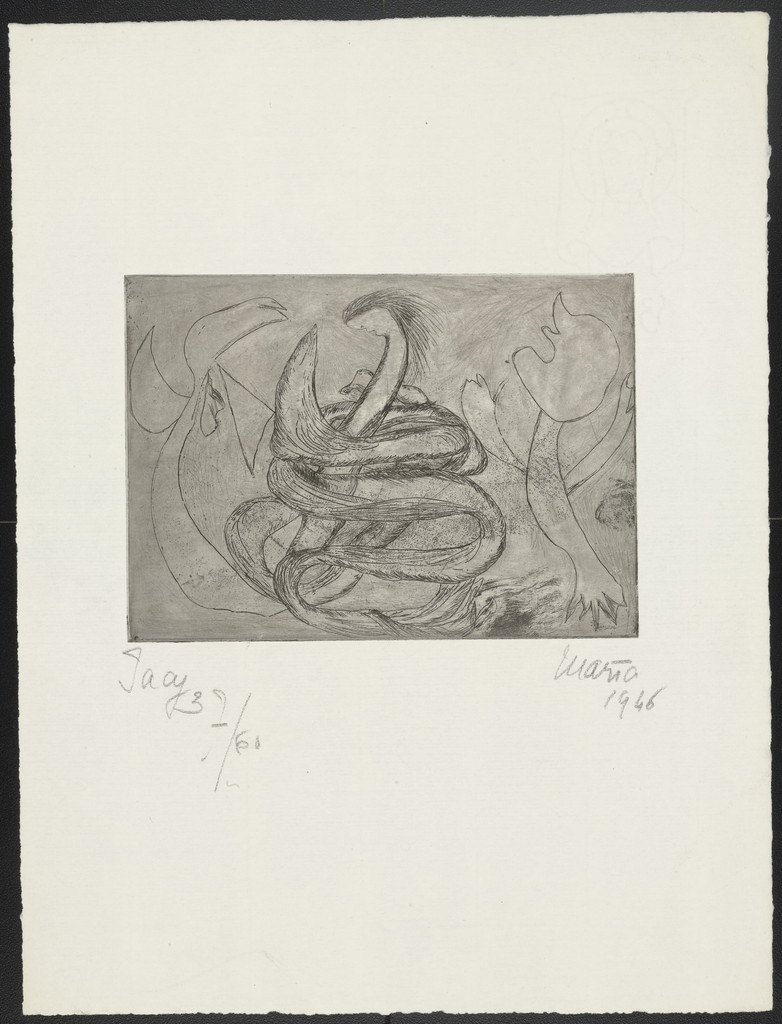

Iacy from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

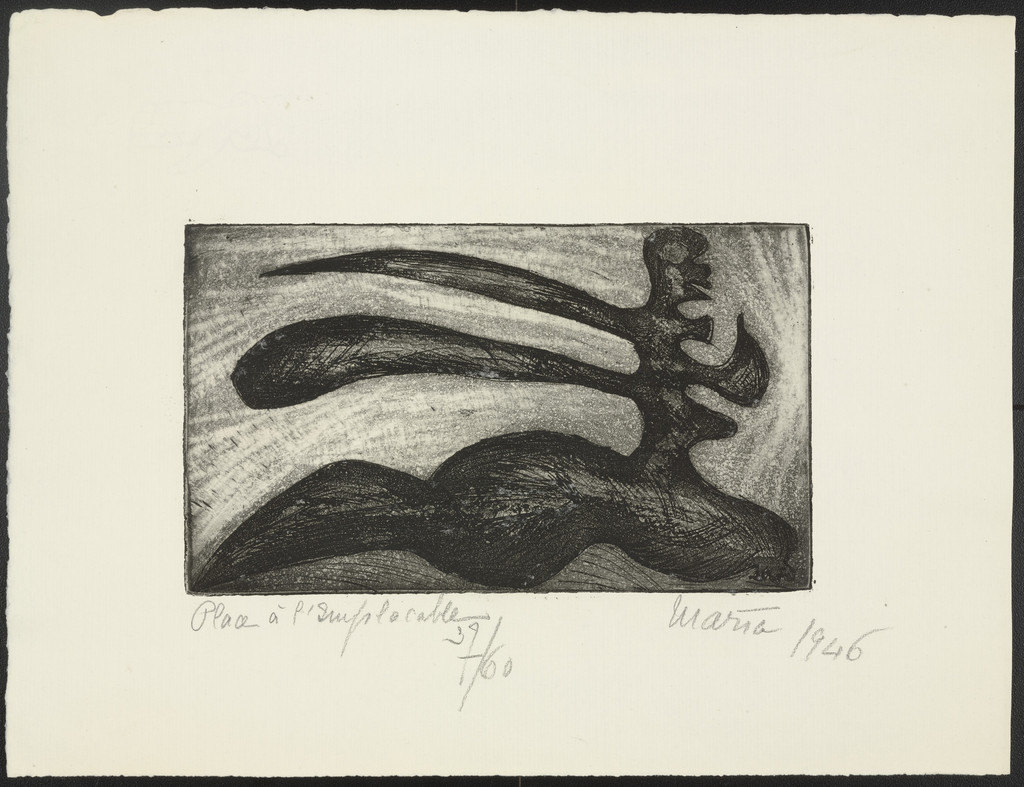

Implacable Place (Place à l'implacable) from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

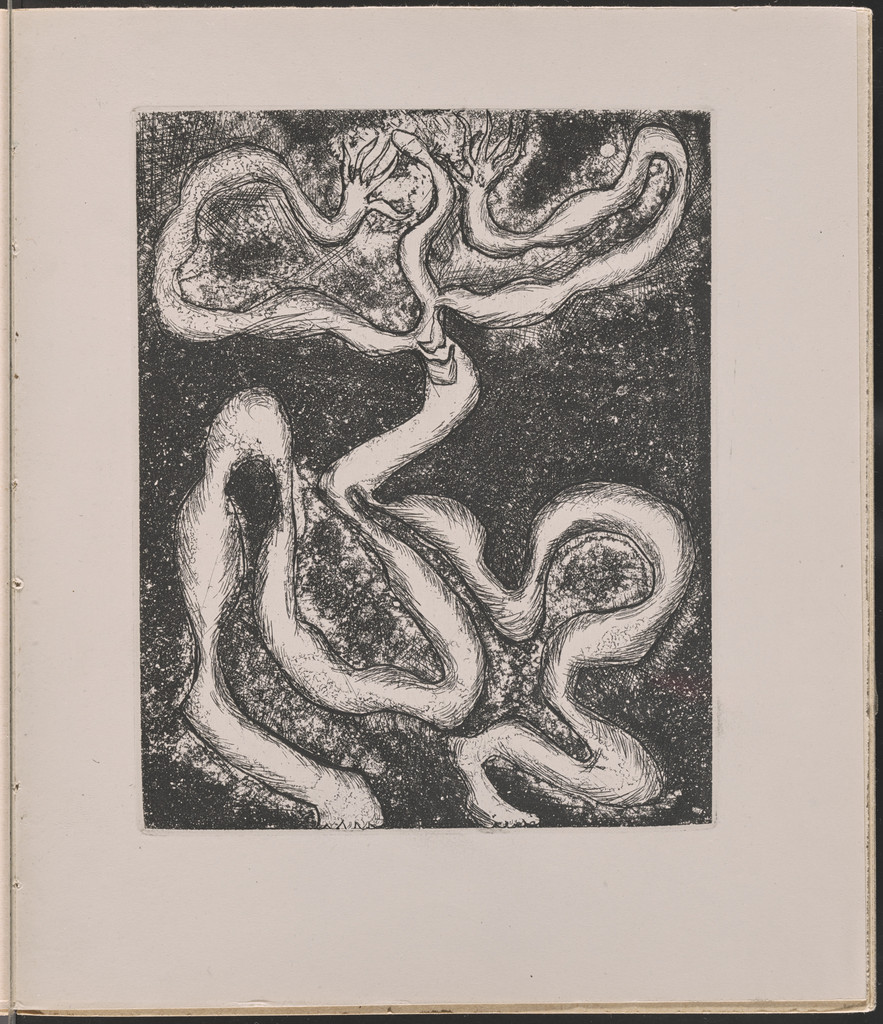

Impossible from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

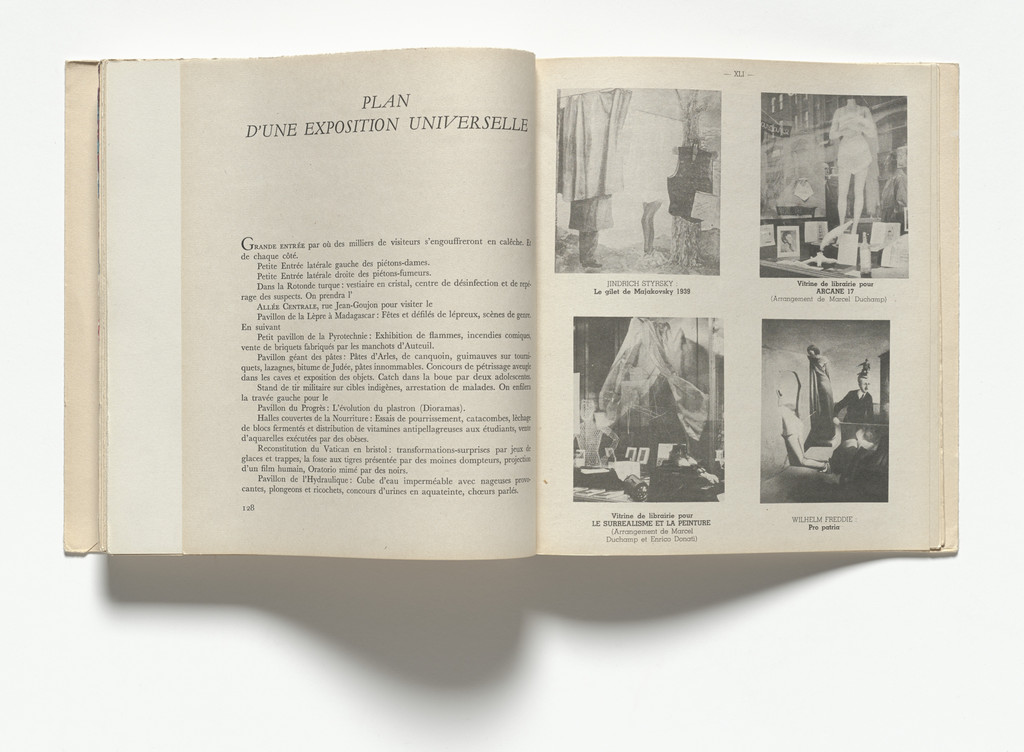

Le Surréalisme en 1947

Jean (Hans) Arp

1947

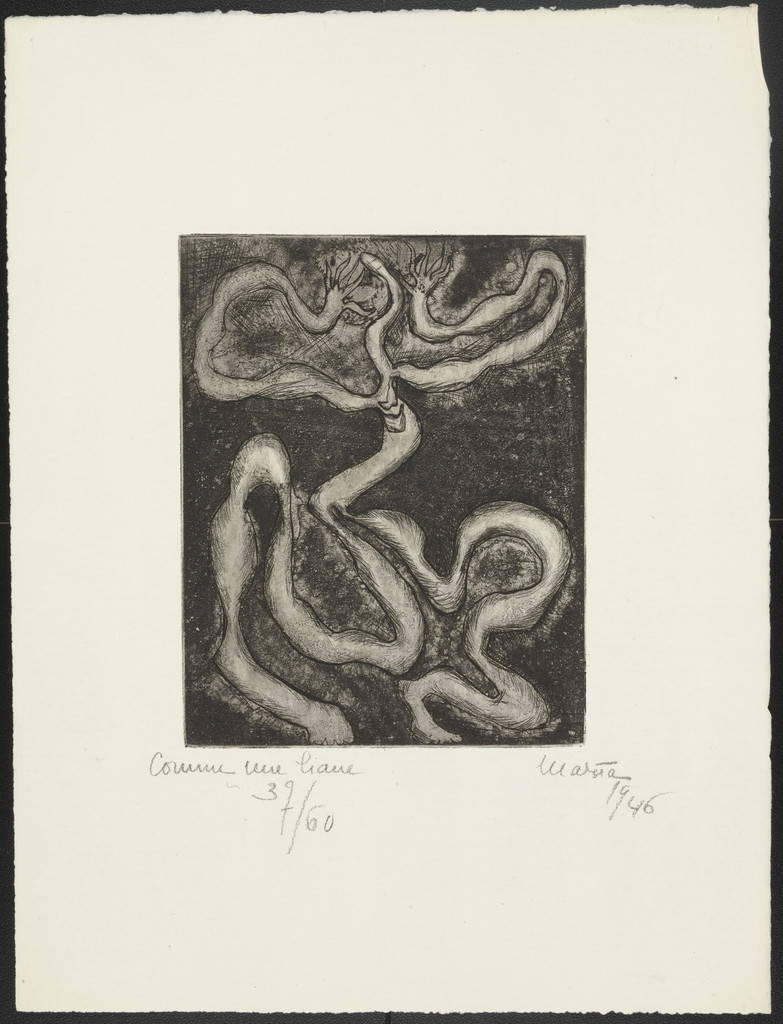

Like a Vine (Comme une liane) from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

Plate from Le Surréalisme en 1947

Maria Martins

1947

The Impossible, III

Maria Martins

1946

The Road; The Shadow; Too Long, Too Narrow

Maria Martins

1946

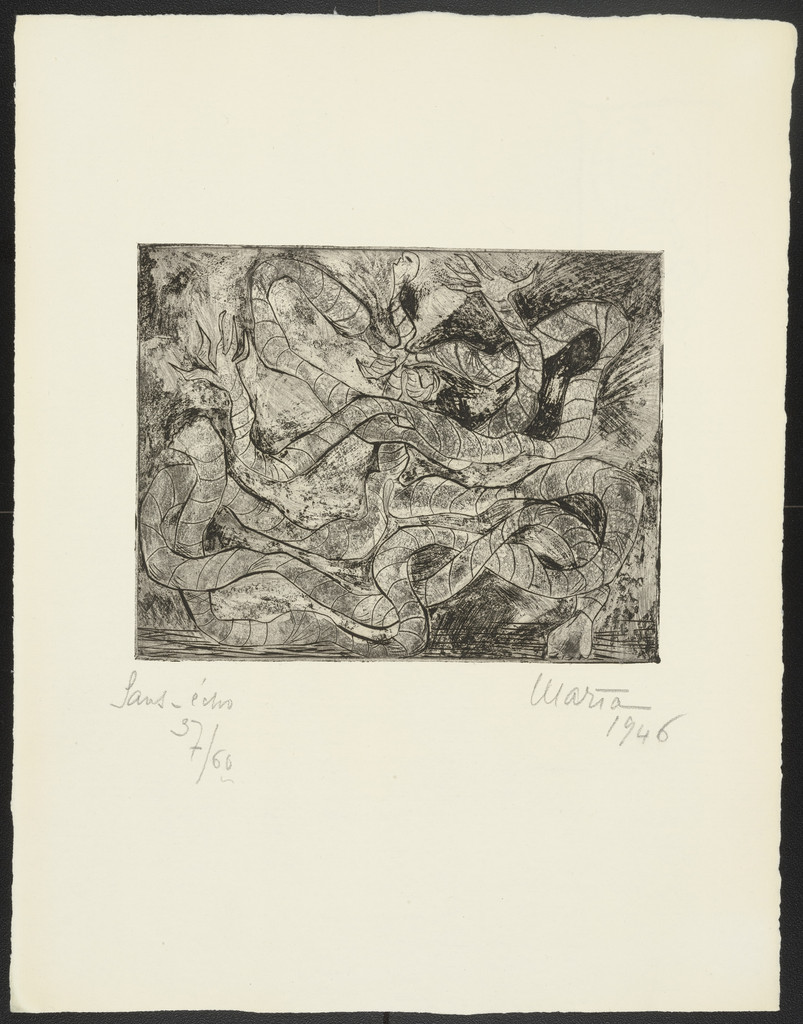

Without Echo (Sans-écho) from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

Wrapper front from Maria 1946

Maria Martins

1946

Exhibitions

10 exhibitionsJan 13, 1942 – Feb 15, 1942

New Acquisitions: Latin-American Art

6 artists

Mar 31, 1943 – Jun 06, 1943

The Latin-American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art

154 artists · 1 curator

May 24, 1944 – Oct 15, 1944

Painting, Sculpture, Prints

133 artists · 1 curator

Jun 20, 1945 – Feb 13, 1946

The Museum Collection of Painting and Sculpture

174 artists

Feb 19, 1946 – May 05, 1946

The Museum Collection of Painting

67 artists

Jul 02, 1946 – Sep 12, 1954

Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphic Arts from the Museum Collection

112 artists · 1 curator

Sep 24, 1946 – Nov 17, 1946

Recent Acquisitions in Painting and Sculpture

11 artists

Dec 21, 1960 – Feb 05, 1961

Recent Acquisitions

222 artists · 3 curators

Feb 16, 1965 – Apr 25, 1965

Recent Acquisitions: Painting and Sculpture

87 artists

Mar 17, 1967 – Jun 04, 1967

Latin-American Art, 19311966, from the Museum Collection

37 artists · 2 curators